Data Transformation

Overview

Teaching: 60 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

How to use dply to transform data in R?

How do I select columns

How can I filter rows

How can I join two data frames?

Objectives

Be able to explore a dataframe

Be able to add, rename, and remove columns.

Be able to filter rows

Be able to append two data frames

Be able to join two data frames

Data transformation

Introduction

Every data analysis you conduct will likely involve manipulating dataframes at some point. Quickly extracting, transforming, and summarizing information from dataframes is an essential R skill. In this part we’ll use Hadley Wickham’s dplyr package, which consolidates and simplifies many of the common operations we perform on dataframes. In addition, much of dplyr key functionality is written in C++ for speed.

if (!require("tidyverse")) install.packages("tidyverse")

library(tidyverse)

Important!

Take careful note of the conflicts message that’s printed when you load the tidyverse. It tells you that dplyr overwrites some functions in base R. If you want to use the base version of these functions after loading dplyr, you’ll need to use their full names:

stats::filter()andstats::lag().

Dataset

We will use the dataset Dataset_S1.txt from the paper “The Influence of Recombination on Human Genetic Diversity”, which contains estimates of population genetics statistics such as nucleotide diversity (e.g., the columns Pi and Theta), recombination (column Recombination), and sequence divergence as estimated by percent identity between human and chimpanzee genomes (column Divergence). Other columns contain information about the sequencing depth (depth), and GC content (percent.GC) for 1kb windows in human chromosome 20. We’ll only work with a few columns in our examples; see the description of Dataset_S1.txt in the original paper for more detail.

Miscellaneous Tips

- Files can be downloaded directly from the Internet into a local folder of your choice using the

download.filefunction. Theread_csvfunction can then be executed to read the downloaded file from the download location, for example,download.file("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/vsbuffalo/bds-files/master/chapter-08-r/Dataset_S1.txt", destfile = "data/Dataset_S1.txt") dvst <- read_csv("data/Dataset_S1.txt")

- Alternatively, you can read files directly from the Internet into R by replacing the file paths with a web address in

read_csv. In doing this no local copy of the csv file is first saved onto your computer. For example,dvst <- read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/vsbuffalo/bds-files/master/chapter-08-r/Dataset_S1.txt")

So, let’s read the file directly into a tbl_df or tibble:

dvst <- read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/vsbuffalo/bds-files/master/chapter-08-r/Dataset_S1.txt")

Parsed with column specification:

cols(

start = col_integer(),

end = col_integer(),

`total SNPs` = col_integer(),

`total Bases` = col_integer(),

depth = col_double(),

`unique SNPs` = col_integer(),

dhSNPs = col_integer(),

`reference Bases` = col_integer(),

Theta = col_double(),

Pi = col_double(),

Heterozygosity = col_double(),

`%GC` = col_double(),

Recombination = col_double(),

Divergence = col_double(),

Constraint = col_integer(),

SNPs = col_integer()

)

Notice the parsing of columns in the file. Also notice that some of the columns names

contain spaces and special characters. We’ll replace them soon to facilitate typing.

Type dvst to look at the dataframe:

dvst

# A tibble: 59,140 x 16

start end `total SNPs` `total Bases` depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs

<int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 55001 56000 0 1894 3.41 0 0

2 56001 57000 5 6683 6.68 2 2

3 57001 58000 1 9063 9.06 1 0

4 58001 59000 7 10256 10.3 3 2

5 59001 60000 4 8057 8.06 4 0

6 60001 61000 6 7051 7.05 2 1

7 61001 62000 7 6950 6.95 2 1

8 62001 63000 1 8834 8.83 1 0

9 63001 64000 1 9629 9.63 1 0

10 64001 65000 3 7999 8.00 1 1

# ... with 59,130 more rows, and 9 more variables: `reference

# Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>, Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>,

# `%GC` <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>, Divergence <dbl>, Constraint <int>,

# SNPs <int>

Because it’s common to work with dataframes with more rows and columns than fit in your screen, tibble

wraps dataframes so that they don’t fill your screen when you print them

(similar to using head()). Notice that the tibble only shows the first few rows and all the columns that

fit on one screen. Run View(dvst), which will open the dataset in the RStudio viewer, to see the whole dataframe.

Also notice the row of three (or four) letter abbreviations under the column names.

These describe the type of each variable:

-

intstands for integers. -

dblstands for doubles, or real numbers. -

fctrstands for factors, which R uses to represent categorical variables with fixed possible values.

There are four other common types of variables that aren’t used in this dataset:

-

chrstands for character vectors, or strings. -

dttmstands for date-times (a date + a time). -

lglstands for logical, vectors that contain onlyTRUEorFALSE. -

datestands for dates.

Although the standard R operations work with tibbles (see below), we’ll learn how to use dplyr functions insted

colnames(dvst)[12] <- "percent.GC" #rename X.GC columns

dvst$GC.binned <- cut(dvst$percent.GC, 5) # create a new column from existing data

dplyr basics

There are five key dplyr functions that allow you to solve the vast majority of data manipulation challenges:

- Pick observations by their values (

filter()). - Reorder the rows (

arrange()). - Pick variables by their names (

select()). - Create new variables with functions of existing variables (

mutate()). - Collapse many values down to a single summary (

summarise()).

None of these functions perform tasks you can’t accomplish with R’s base functions. But dplyr’s advantage is in the added consistency, speed, and versatility of its data manipulation interface.

dplyr functions be used in conjunction with group_by() which changes the scope of each function from operating

on the entire dataset to operating on it group-by-group. These six functions provide the verbs for a language of

data manipulation.

All verbs work similarly:

-

The first argument is a data frame.

-

The subsequent arguments describe what to do with the data frame, using the variable names (without quotes).

-

The result is a new data frame.

Together these properties make it easy to chain together multiple simple steps to achieve a complex result. Let’s dive in and see how these verbs work.

===

Use filter() to filter rows

Let’s say we used summary to get an idea about the total number of SNPs in different windows:

summary(dvst$`total SNPs`)

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

0.000 3.000 7.000 8.906 12.000 93.000

# or with dplyr

select(dvst,`total SNPs`) %>% summary()

total SNPs

Min. : 0.000

1st Qu.: 3.000

Median : 7.000

Mean : 8.906

3rd Qu.:12.000

Max. :93.000

We see that this varies quite considerably across all windows on chromosome 20 and the data are right-skewed:

the third quartile is 12 SNPs, but the maximum is 93 SNPs. Often we want to investigate such outliers more

closely. We can use filter() to extract the rows of our dataframe based on their values. The first argument

is the name of the data frame. The second and subsequent arguments are the expressions that filter the data frame.

filter(dvst,`total SNPs` >= 85)

# A tibble: 3 x 17

start end `total SNPs` `total Bases` depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs

<int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 2621001 2622000 93 11337 11.3 13 10

2 13023001 13024000 88 11784 11.8 11 1

3 47356001 47357000 87 12505 12.5 9 7

# ... with 10 more variables: `reference Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>,

# Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>, percent.GC <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>,

# Divergence <dbl>, Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>, GC.binned <fct>

We can build more elaborate queries by using multiple filters. For example, suppose we wanted to see all windows where Pi (nucleotide diversity) is greater than 16 and percent GC is greater than 80. We’d use:

filter(dvst, Pi > 16, percent.GC > 80)

# A tibble: 3 x 17

start end `total SNPs` `total Bases` depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs

<int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 63097001 63098000 5 947 2.39 2 1

2 63188001 63189000 2 1623 3.21 2 0

3 63189001 63190000 5 1395 1.89 3 2

# ... with 10 more variables: `reference Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>,

# Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>, percent.GC <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>,

# Divergence <dbl>, Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>, GC.binned <fct>

When you run that line of code, dplyr executes the filtering operation and returns a new data frame.

Note, dplyr functions never modify their inputs, so if you want to save the result, you’ll need to use the

assignment operator, <-:

new_df <- filter(dvst, Pi > 16, percent.GC > 80)

Miscellaneous Tips

R either prints out the results, or saves them to a variable. If you want to do both, you can wrap the assignment in parentheses:

(search_db <- filter(dvst, Pi > 16, percent.GC > 80))# A tibble: 3 x 17 start end `total SNPs` `total Bases` depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int> 1 63097001 63098000 5 947 2.39 2 1 2 63188001 63189000 2 1623 3.21 2 0 3 63189001 63190000 5 1395 1.89 3 2 # ... with 10 more variables: `reference Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>, # Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>, percent.GC <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>, # Divergence <dbl>, Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>, GC.binned <fct>

Comparisons

To use filtering effectively, you have to know how to select the observations that you want using the

comparison operators. R provides the standard suite: >, >=, <, <=, != (not equal), and == (equal).

Common pitfalls

When you’re starting out with R, the easiest mistake to make is to use

=instead of==when testing for equality. When this > happens you’ll get an informative error:filter(dvst, `total SNPs` = 0)Error: `total SNPs` (`total SNPs = 0`) must not be named, do you need `==`?There’s another common problem you might encounter when using

==: floating point numbers. These results might surprise you!sqrt(2) ^ 2 == 2[1] FALSE1/49 * 49 == 1[1] FALSEComputers use finite precision arithmetic (they obviously can’t store an infinite number of digits!) so remember that every number you see is an approximation. Instead of relying on

==, usenear():near(sqrt(2) ^ 2, 2)[1] TRUEnear(1 / 49 * 49, 1)[1] TRUE

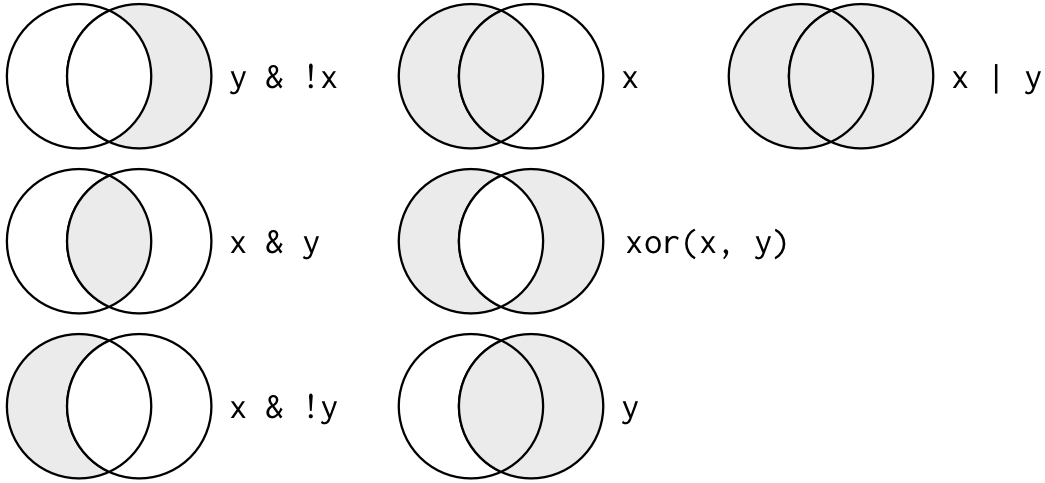

Logical operators

Multiple arguments to filter() are combined with “and”: every expression must be true in order for a

row to be included in the output. For other types of combinations, you’ll need to use Boolean operators

yourself: & is “and”, | is “or”, and ! is “not”. Figure \@ref(fig:bool-ops) shows the complete set

of Boolean operations.

If you are looking for multiple values within a certain column, use the x %in% y shortcut. This will

select every row where x is one of the values in y:

filter(dvst, total.SNPs %in% c(0,2))

Notice, how the following search gives some unexpected results:

filter(dvst, total.SNPs == 0 | 2)

Finally, whenever you start using complicated, multipart expressions in filter(), consider making them explicit

variables instead. That makes it much easier to check your work. We’ll learn how to create new variables shortly.

Missing values

One important feature of R that can make comparison tricky are missing values, or NAs (“not availables”).

NA represents an unknown value so missing values are “contagious”: almost any operation involving an unknown

value will also be unknown.

NA > 5

[1] NA

10 == NA

[1] NA

NA + 10

[1] NA

NA / 2

[1] NA

NA == NA

[1] NA

filter() only includes rows where the condition is TRUE; it excludes both FALSE and NA values. If you want

to preserve missing values, ask for them explicitly:

filter(dvst, is.na(Divergence))

# A tibble: 0 x 17

# ... with 17 variables: start <int>, end <int>, `total SNPs` <int>,

# `total Bases` <int>, depth <dbl>, `unique SNPs` <int>, dhSNPs <int>,

# `reference Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>, Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>,

# percent.GC <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>, Divergence <dbl>,

# Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>, GC.binned <fct>

## compare to

dvst %>% add_row() %>% filter(is.na(Divergence))

# A tibble: 1 x 17

start end `total SNPs` `total Bases` depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs

<int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

# ... with 10 more variables: `reference Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>,

# Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>, percent.GC <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>,

# Divergence <dbl>, Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>, GC.binned <fct>

Exercises

-

Find all windows

- With the lowest/highest GC content

- That have 0 total SNPs

- That are incomplete (<1000 bp)

- That have the highest divergence with the chimp

- That have less than 5% GC difference from the mean

-

Another useful dplyr filtering helper is

between(). What does it do? Can you use it to simplify the code needed to answer the previous challenges?

===

Use mutate() to add new variables

It’s often useful to add new columns that are functions of existing columns (notice, how we used dvst$GC.binned <- cut(dvst$percent.GC, 5) above). That’s the job of mutate().

mutate() always adds new columns at the end of your dataset. Remember that when you’re in RStudio, the easiest

way to see all the columns is View().

Here we’ll add an additional column that indicates whether a window is in the centromere region. The positions of the chromosome 20 centromere (based on Giemsa banding) are 25,800,000 to 29,700,000 (see this chapter’s README on GitHub to see how these coordinates were found). To append a column called cent that has TRUE/FALSE values indicating whether the current window is fully within a centromeric region we’ll use comparison and logical operations:

mutate(dvst, cent = start >= 25800000 & end <= 29700000)

# A tibble: 59,140 x 18

start end `total SNPs` `total Bases` depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs

<int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 55001 56000 0 1894 3.41 0 0

2 56001 57000 5 6683 6.68 2 2

3 57001 58000 1 9063 9.06 1 0

4 58001 59000 7 10256 10.3 3 2

5 59001 60000 4 8057 8.06 4 0

6 60001 61000 6 7051 7.05 2 1

7 61001 62000 7 6950 6.95 2 1

8 62001 63000 1 8834 8.83 1 0

9 63001 64000 1 9629 9.63 1 0

10 64001 65000 3 7999 8.00 1 1

# ... with 59,130 more rows, and 11 more variables: `reference

# Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>, Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>,

# percent.GC <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>, Divergence <dbl>,

# Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>, GC.binned <fct>, cent <lgl>

dvst

# A tibble: 59,140 x 17

start end `total SNPs` `total Bases` depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs

<int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 55001 56000 0 1894 3.41 0 0

2 56001 57000 5 6683 6.68 2 2

3 57001 58000 1 9063 9.06 1 0

4 58001 59000 7 10256 10.3 3 2

5 59001 60000 4 8057 8.06 4 0

6 60001 61000 6 7051 7.05 2 1

7 61001 62000 7 6950 6.95 2 1

8 62001 63000 1 8834 8.83 1 0

9 63001 64000 1 9629 9.63 1 0

10 64001 65000 3 7999 8.00 1 1

# ... with 59,130 more rows, and 10 more variables: `reference

# Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>, Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>,

# percent.GC <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>, Divergence <dbl>,

# Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>, GC.binned <fct>

Challenge 3

- Why don’t we see the column in the dataset?

Solution

As discussed above, dplyr functions never modify their inputs

- What standard R command can we use to create a new column in an existing dataframe?

Solution

d_df$cent <- d_df$start >= 25800000 & d_df$end <= 29700000Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): object 'd_df' not found

- How many windows fall into this centromeric region?

Solution

Use

filter()filter(d_df,cent==TRUE)Error in filter(d_df, cent == TRUE): object 'd_df' not foundor sum()

sum(d_df$cent)Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): object 'd_df' not found

In the dataset we are using, the diversity estimate Pi is measured per sampling window (1kb) and scaled up by 10x (see supplementary Text S1 for more details). It would be useful to have this scaled as per basepair nucleotide diversity (so as to make the scale more intuitive).

mutate(dvst, diversity = Pi / (10*1000)) # rescale, removing 10x and making per bp

# A tibble: 59,140 x 18

start end `total SNPs` `total Bases` depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs

<int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 55001 56000 0 1894 3.41 0 0

2 56001 57000 5 6683 6.68 2 2

3 57001 58000 1 9063 9.06 1 0

4 58001 59000 7 10256 10.3 3 2

5 59001 60000 4 8057 8.06 4 0

6 60001 61000 6 7051 7.05 2 1

7 61001 62000 7 6950 6.95 2 1

8 62001 63000 1 8834 8.83 1 0

9 63001 64000 1 9629 9.63 1 0

10 64001 65000 3 7999 8.00 1 1

# ... with 59,130 more rows, and 11 more variables: `reference

# Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>, Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>,

# percent.GC <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>, Divergence <dbl>,

# Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>, GC.binned <fct>, diversity <dbl>

Notice, that we can combine the two operations in a single command (and also save the result):

dvst <- mutate(dvst,

diversity = Pi / (10*1000),

cent = start >= 25800000 & end <= 29700000

)

If you only want to keep the new variables, use transmute():

transmute(dvst,

diversity = Pi / (10*1000),

cent = start >= 25800000 & end <= 29700000

)

# A tibble: 59,140 x 2

diversity cent

<dbl> <lgl>

1 0 F

2 0.00104 F

3 0.000199 F

4 0.000956 F

5 0.000851 F

6 0.000912 F

7 0.000806 F

8 0.000206 F

9 0.000188 F

10 0.000541 F

# ... with 59,130 more rows

Useful creation functions

There are many functions for creating new variables that you can use with

mutate(). The key property is that the function must be vectorised: it must take a vector of values as input, return a vector with the same number of values as output. There’s no way to list every possible function that you might use, but here’s a selection of functions that are frequently useful:

Arithmetic operators:

+,-,*,/,^. These are all vectorised, using the so called “recycling rules”.Modular arithmetic:

%/%(integer division) and%%(remainder), wherex == y * (x %/% y) + (x %% y). Modular arithmetic is a handy tool because it allows you to break integers up into pieces.Logs:

log(),log2(),log10(). Logarithms are an incredibly useful transformation for dealing with data that ranges across multiple orders of magnitude. They also convert multiplicative relationships to additive.Offsets:

lead()andlag()allow you to refer to leading or lagging values. This allows you to compute running differences (e.g.x - lag(x)) or find when values change (x != lag(x)). They are most useful in conjunction withgroup_by(), which you’ll learn about shortly.Cumulative and rolling aggregates: R provides functions for running sums, products, mins and maxes:

cumsum(),cumprod(),cummin(),cummax(); and dplyr providescummean()for cumulative means.Logical comparisons,

<,<=,>,>=,!=, which you learned about earlier. If you’re doing a complex sequence of logical operations it’s often a good idea to store the interim values in new variables so you can check that each step is working as expected.Ranking:

min_rank()does the most usual type of ranking (e.g. 1st, 2nd, 2nd, 4th). The default gives smallest values the small ranks; usedesc(x)to give the largest values the smallest ranks. Ifmin_rank()doesn’t do what you need, look at the variantsrow_number(),dense_rank(),percent_rank(),cume_dist(),ntile(). See their help pages for more details.

===

Use arrange() to arrange rows

arrange() works similarly to filter() except that instead of selecting rows, it changes their order.

It takes a data frame and a set of column names (or more complicated expressions) to order by. If you

provide more than one column name, each additional column will be used to break ties in the values of

preceding columns:

arrange(dvst, cent, percent.GC)

# A tibble: 59,140 x 19

start end `total SNPs` `total Bases` depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs

<int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 43448001 43449000 5 690 2.66 5 0

2 14930001 14931000 19 3620 4.57 7 1

3 37777001 37778000 3 615 1.12 3 0

4 54885001 54886000 1 2298 3.69 1 0

5 54888001 54889000 15 3823 3.87 11 1

6 41823001 41824000 15 6950 6.95 10 4

7 50530001 50531000 10 7293 7.29 2 2

8 39612001 39613000 13 8254 8.25 5 3

9 55012001 55013000 7 7028 7.03 7 0

10 22058001 22059000 4 281 1.20 4 0

# ... with 59,130 more rows, and 12 more variables: `reference

# Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>, Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>,

# percent.GC <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>, Divergence <dbl>,

# Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>, GC.binned <fct>, diversity <dbl>,

# cent <lgl>

Use desc() to re-order by a column in descending order:

arrange(dvst, desc(cent), percent.GC)

# A tibble: 59,140 x 19

start end `total SNPs` `total Bases` depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs

<int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 25869001 25870000 10 7292 7.29 6 2

2 29318001 29319000 2 6192 6.19 2 0

3 29372001 29373000 5 7422 7.42 3 2

4 26174001 26175000 1 7816 7.82 1 0

5 26182001 26183000 2 6630 6.63 1 1

6 25924001 25925000 30 7127 7.13 15 8

7 26155001 26156000 0 9449 9.45 0 0

8 25926001 25927000 21 8197 8.20 13 6

9 29519001 29520000 15 8135 8.14 13 2

10 25901001 25902000 9 9126 9.13 5 2

# ... with 59,130 more rows, and 12 more variables: `reference

# Bases` <int>, Theta <dbl>, Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>,

# percent.GC <dbl>, Recombination <dbl>, Divergence <dbl>,

# Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>, GC.binned <fct>, diversity <dbl>,

# cent <lgl>

Note, that missing values are always sorted at the end!

Exercises

- How could you use

arrange()to sort all missing values to the start? (Hint: useis.na()).

===

Use select() to select columns and rename() to rename them

It’s not uncommon to get datasets with hundreds or even thousands of variables. In this case, the first

challenge is often narrowing in on the variables you’re actually interested in. select() allows you to

rapidly zoom in on a useful subset using operations based on the names of the variables.

select() is not terribly useful with our data because they only have a few variables, but you can still

get the general idea:

# Select columns by name

select(dvst, start, end, Divergence)

# A tibble: 59,140 x 3

start end Divergence

<int> <int> <dbl>

1 55001 56000 0.00301

2 56001 57000 0.0180

3 57001 58000 0.00701

4 58001 59000 0.0120

5 59001 60000 0.0240

6 60001 61000 0.0160

7 61001 62000 0.0120

8 62001 63000 0.0150

9 63001 64000 0.00901

10 64001 65000 0.00701

# ... with 59,130 more rows

# Select all columns between year and day (inclusive)

select(dvst, depth:Pi)

# A tibble: 59,140 x 6

depth `unique SNPs` dhSNPs `reference Bases` Theta Pi

<dbl> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <dbl>

1 3.41 0 0 556 0 0

2 6.68 2 2 1000 8.01 10.4

3 9.06 1 0 1000 3.51 1.99

4 10.3 3 2 1000 9.93 9.56

5 8.06 4 0 1000 12.9 8.51

6 7.05 2 1 1000 7.82 9.12

7 6.95 2 1 1000 8.60 8.06

8 8.83 1 0 1000 4.01 2.06

9 9.63 1 0 1000 3.37 1.88

10 8.00 1 1 1000 4.16 5.41

# ... with 59,130 more rows

# Select all columns except those from year to day (inclusive)

select(dvst, -(start:percent.GC))

# A tibble: 59,140 x 7

Recombination Divergence Constraint SNPs GC.binned diversity cent

<dbl> <dbl> <int> <int> <fct> <dbl> <lgl>

1 0.00960 0.00301 0 0 (51.6,68.5] 0 F

2 0.00960 0.0180 0 0 (34.7,51.6] 0.00104 F

3 0.00960 0.00701 0 0 (34.7,51.6] 0.000199 F

4 0.00960 0.0120 0 0 (34.7,51.6] 0.000956 F

5 0.00960 0.0240 0 0 (34.7,51.6] 0.000851 F

6 0.00960 0.0160 0 0 (34.7,51.6] 0.000912 F

7 0.00960 0.0120 0 0 (34.7,51.6] 0.000806 F

8 0.00960 0.0150 0 0 (34.7,51.6] 0.000206 F

9 0.00960 0.00901 58 1 (34.7,51.6] 0.000188 F

10 0.00958 0.00701 0 1 (17.7,34.7] 0.000541 F

# ... with 59,130 more rows

There are a number of helper functions you can use within select():

-

starts_with("abc"): matches names that begin with “abc”. -

ends_with("xyz"): matches names that end with “xyz”. -

contains("ijk"): matches names that contain “ijk”. -

matches("(.)\\1"): selects variables that match a regular expression. This one matches any variables that contain repeated characters. You’ll learn more about regular expressions in [strings]. -

num_range("x", 1:3)matchesx1,x2andx3.

See ?select for more details.

select() can also be used to rename variables, but it’s rarely useful because it drops all of the variables

not explicitly mentioned. Instead, use rename(), which is a variant of select() that keeps all the

variables that aren’t explicitly mentioned:

dvst <- rename(dvst, total.SNPs = `total SNPs`,

total.Bases = `total Bases`,

unique.SNPs = `unique SNPs`,

reference.Bases = `reference Bases`) #renaming all the columns with spaces!

colnames(dvst)

[1] "start" "end" "total.SNPs"

[4] "total.Bases" "depth" "unique.SNPs"

[7] "dhSNPs" "reference.Bases" "Theta"

[10] "Pi" "Heterozygosity" "percent.GC"

[13] "Recombination" "Divergence" "Constraint"

[16] "SNPs" "GC.binned" "diversity"

[19] "cent"

Another option is to use select() in conjunction with the everything() helper. This is useful if you

have a handful of variables you’d like to move to the start of the data frame.

select(dvst, cent, everything())

# A tibble: 59,140 x 19

cent start end total.SNPs total.Bases depth unique.SNPs dhSNPs

<lgl> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 F 55001 56000 0 1894 3.41 0 0

2 F 56001 57000 5 6683 6.68 2 2

3 F 57001 58000 1 9063 9.06 1 0

4 F 58001 59000 7 10256 10.3 3 2

5 F 59001 60000 4 8057 8.06 4 0

6 F 60001 61000 6 7051 7.05 2 1

7 F 61001 62000 7 6950 6.95 2 1

8 F 62001 63000 1 8834 8.83 1 0

9 F 63001 64000 1 9629 9.63 1 0

10 F 64001 65000 3 7999 8.00 1 1

# ... with 59,130 more rows, and 11 more variables: reference.Bases <int>,

# Theta <dbl>, Pi <dbl>, Heterozygosity <dbl>, percent.GC <dbl>,

# Recombination <dbl>, Divergence <dbl>, Constraint <int>, SNPs <int>,

# GC.binned <fct>, diversity <dbl>

===

Use summarise() to make summaries

The last key verb is summarise(). It collapses a data frame to a single row:

summarise(dvst, GC = mean(percent.GC, na.rm = TRUE), averageSNPs=mean(total.SNPs, na.rm = TRUE), allSNPs=sum(total.SNPs))

# A tibble: 1 x 3

GC averageSNPs allSNPs

<dbl> <dbl> <int>

1 44.1 8.91 526693

summarise() is not terribly useful unless we pair it with group_by(). This changes the unit of analysis from the complete dataset to individual groups. Then, when you use the dplyr verbs on a grouped data frame they’ll be automatically applied “by group”. For example, if we applied exactly the same code to a data frame grouped by position related to centromere:

by_cent <- group_by(dvst, cent)

summarise(by_cent, GC = mean(percent.GC, na.rm = TRUE), averageSNPs=mean(total.SNPs, na.rm = TRUE), allSNPs=sum(total.SNPs))

# A tibble: 2 x 4

cent GC averageSNPs allSNPs

<lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <int>

1 F 44.2 8.87 518743

2 T 39.7 11.6 7950

Subsetting columns can be a useful way to summarize data across two different conditions. For example, we might be curious if the average depth in a window (the depth column) differs between very high GC content windows (greater than 80%) and all other windows:

by_GC <- group_by(dvst, percent.GC >= 80)

summarize(by_GC, depth=mean(depth))

# A tibble: 2 x 2

`percent.GC >= 80` depth

<lgl> <dbl>

1 F 8.18

2 T 2.24

This is a fairly large difference, but it’s important to consider how many windows this includes.

Whenever you do any aggregation, it’s always a good idea to include either a count (n()),

or a count of non-missing values (sum(!is.na(x))). That way you can check that you’re not

drawing conclusions based on very small amounts of data:

summarize(by_GC, mean_depth=mean(depth), n_rows=n())

# A tibble: 2 x 3

`percent.GC >= 80` mean_depth n_rows

<lgl> <dbl> <int>

1 F 8.18 59131

2 T 2.24 9

Challenge 6

As another example, consider looking at Pi by windows that fall in the centromere and those that do not. Does the centromer have higher nucleotide diversity than other regions in these data?

Solutions to challenge 6

Because cent is a logical vector, we can group by it directly:

by_cent <- group_by(dvst, cent) summarize(by_cent, nt_diversity=mean(diversity), min=which.min(diversity), n_rows=n())# A tibble: 2 x 4 cent nt_diversity min n_rows <lgl> <dbl> <int> <int> 1 F 0.00123 1 58455 2 T 0.00204 1 685Indeed, the centromere does appear to have higher nucleotide diversity than other regions in this data.

Useful summary functions

Just using means, counts, and sum can get you a long way, but R provides many other useful summary functions:

- Measures of location: we’ve used

mean(x), butmedian(x)is also useful.- Measures of spread:

sd(x),IQR(x),mad(x). The mean squared deviation, or standard deviation or sd for short, is the standard measure of spread. The interquartile rangeIQR()and median absolute deviationmad(x)are robust equivalents that may be more useful if you have outliers.- Measures of rank:

min(x),quantile(x, 0.25),max(x). Quantiles are a generalisation of the median. For example,quantile(x, 0.25)will find a value ofxthat is greater than 25% of the values, and less than the remaining 75%.- Measures of position:

first(x),nth(x, 2),last(x). These work similarly tox[1],x[2], andx[length(x)]but let you set a default value if that position does not exist (i.e. you’re trying to get the 3rd element from a group that only has two elements).- Counts: You’ve seen

n(), which takes no arguments, and returns the size of the current group. To count the number of non-missing values, usesum(!is.na(x)). To count the number of distinct (unique) values, usen_distinct(x).- Counts and proportions of logical values:

sum(x > 10),mean(y == 0). When used with numeric functions,TRUEis converted to 1 andFALSEto 0. This makessum()andmean()very useful:sum(x)gives the number ofTRUEs inx, andmean(x)gives the proportion.

Together group_by() and summarise() provide one of the tools that you’ll use most commonly when working with dplyr: grouped summaries. But before we go any further with this, we need to introduce a powerful new idea: the pipe.

Combining multiple operations with the pipe

It looks like we have been creating and naming several intermediate files in our anlysis, even though we didn’t care about them. Naming things is hard, so this slows down our analysis.

There’s another way to tackle the same problem with the pipe, %>%:

dvst %>%

rename(GC.percent = percent.GC) %>%

group_by(GC.percent >= 80) %>%

summarize(mean_depth=mean(depth, na.rm = TRUE), n_rows=n())

# A tibble: 2 x 3

`GC.percent >= 80` mean_depth n_rows

<lgl> <dbl> <int>

1 F 8.18 59131

2 T 2.24 9

This focuses on the transformations, not what’s being transformed.

You can read it as a series of imperative statements: group, then summarise, then filter,

where %>% stands for “then”.

Behind the scenes, x %>% f(y) turns into f(x, y), and x %>% f(y) %>% g(z) turns into

g(f(x, y), z) and so on.

Working with the pipe is one of the key criteria for belonging to the tidyverse. The only exception is ggplot2: it was written before the pipe was discovered. However, the next iteration of ggplot2, ggvis, will use the pipe.

RStudio Tip

A shortcut for %>% is available in the newest RStudio releases under the keybinding CTRL + SHIFT + M (or CMD + SHIFT + M for OSX).

You can also review the set of available keybindings when within RStudio with ALT + SHIFT + K. ```

Missing values

You may have wondered about the

na.rmargument we used above. What happens if we don’t set it? We may get a lot of missing values! That’s because aggregation functions obey the usual rule of missing values: if there’s any missing value in the input, the output will be a missing value. Fortunately, all aggregation functions have anna.rmargument which removes the missing values prior to computation: We could have also removed all the rows that have uknown position value prior to the analysis with thefilter(!is.na())command

Grouping by multiple variables

When you group by multiple variables, each summary peels off one level of the grouping. That makes it easy to progressively roll up a dataset:

daily <- group_by(flights, year, month, day)

Error in group_by(flights, year, month, day): object 'flights' not found

(per_day <- summarise(daily, flights = n()))

Error in summarise(daily, flights = n()): object 'daily' not found

(per_month <- summarise(per_day, flights = sum(flights)))

Error in summarise(per_day, flights = sum(flights)): object 'per_day' not found

(per_year <- summarise(per_month, flights = sum(flights)))

Error in summarise(per_month, flights = sum(flights)): object 'per_month' not found

Be careful when progressively rolling up summaries: it’s OK for sums and counts, but you need to think about weighting means and variances, and it’s not possible to do it exactly for rank-based statistics like the median. In other words, the sum of groupwise sums is the overall sum, but the median of groupwise medians is not the overall median.

Ungrouping

If you need to remove grouping, and return to operations on ungrouped data, use ungroup().

daily %>%

ungroup() %>% # no longer grouped by date

summarise(flights = n()) # all flights

Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): object 'daily' not found

Exercises

- What does the

sortargument tocount()do. When might you use it?

Grouped mutates (and filters)

Grouping is most useful in conjunction with summarise(), but you can also do convenient operations with mutate() and filter():

-

Find the worst members of each group:

flights_sml %>% group_by(year, month, day) %>% filter(rank(desc(arr_delay)) < 10)Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): object 'flights_sml' not found -

Find all groups bigger than a threshold:

popular_dests <- flights %>% group_by(dest) %>% filter(n() > 365)Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): object 'flights' not foundpopular_destsError in eval(expr, envir, enclos): object 'popular_dests' not found -

Standardise to compute per group metrics:

popular_dests %>% filter(arr_delay > 0) %>% mutate(prop_delay = arr_delay / sum(arr_delay)) %>% select(year:day, dest, arr_delay, prop_delay)Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): object 'popular_dests' not found

A grouped filter is a grouped mutate followed by an ungrouped filter. I generally avoid them except for quick and dirty manipulations: otherwise it’s hard to check that you’ve done the manipulation correctly.

Functions that work most naturally in grouped mutates and filters are known as window functions (vs. the summary functions used for summaries). You can learn more about useful window functions in the corresponding vignette: vignette("window-functions").

Exercises

- Refer back to the lists of useful mutate and filtering functions. Describe how each operation changes when you combine it with grouping.

Key Points

Read in a csv file using

read_csv()View a dataframe with

ViewUse

filter()to pick observations by their valuesUse

arrange()to order the rowsUse

select()to pick variables by their namesUse

mutate()to create new variables with functions of existing variablesUse

summarize()to collapse many values down to a single summary