tutorials

GIT QUICK INTRO

Based on chapter 5 from Vince Buffalo’s book “Bioinformatics Data Skills”

Comics are from https://imgs.xkcd.com/comics

Why GIT?

- Allows You to Keep Snapshots of Your Project

- Helps You Keep Track of Important Changes to Code

- Helps Keep Software Organized and Available After People Leave

Installing Git

If you’re on OS X or Linux, git should be already installed (use Homebrew (e.g., brew install git) or apt-get (e.g., apt-get install git), respectively, if you need to update). On Windows, install Git for Windows. Finally, you can always visit the Git website for both source code and executable versions of Git as well as multiple learning resources.

Basic Git

Git Setup

Because Git is meant to help with collaborative editing of files, you need to tell Git who you are and what your email address is. To do this, use:

git config --global user.name "Sewall Wright"

git config --global user.email "swright@adaptivelandscape.org"

Make sure to use your own name and email, or course.

Another useful Git setting to enable now is terminal colors:

git config --global color.ui true

Creating Repositories: git init and git clone

To get started with Git, we first need to create a Git repository. There are two primary ways to it: by initializing one from an existing directory, or cloning a repository that exists elsewhere. We will start with the first :)

First, let’s create a new directory in your home directory (or your preferred location):

mkdir -p ~/EEOB563/labs

Now, go to this directory and initialize it as a git repository:

cd ~/EEOB563/labs

git init.

Tracking Files in Git: git add and git status I

Although you’ve initialized the EEOB563/labs as a Git repository, Git doesn’t automati‐ cally begin tracking every file in this directory. Rather, you need to tell Git which files to track using the subcommand git add.

But before doing it, let’s check the status of our directory:

git status

The command will tell you that we are on branch master, that there were no previous commits (“Initial commit”) and that there is nothing to commit and no files in the direcotry.

Let’s create a new file:

echo # My brand new Git repository" > README.md

and check the status again:

git status

We can see now that we have an untracked file. We use git add command to tell Git to track it:

git add README.md

Now Git is tracking the file and if we made a commit now, a snapshot of the file would be created.

Staging Files in Git: git add and git status II

Here comes a confusing part: git add command is used both to track files and to stage changes to be included in the next commit. But to make it confusing, we have to add another file to our directory:

touch empty

Now, modify the README.md file (e.g., echo '**Git** can be confusing!' >> README.md) and make a commit. If you compare your committed file and your current file (git diff) you’ll see that the previous version of the file has been committed! To include the latest changes, you’ll need to explicitly stage them using git add again. But we have to learn how to make a commit first!

Taking a Snapshot of Your Project: git commit

Modify the file as explained above and commit the changes with the commit command:

git commit -m "First commit"

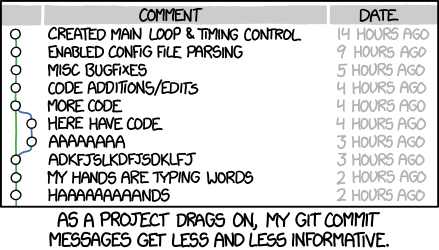

Notice, that we include a message in our commits. If you try to skip it, a default text editor (likely vi) will open. Also notice that this message should be informative!

git diff shows you the difference between the files in your working directory and what’s been staged. If none of your changes have been staged, git diff shows the difference between your last commit and the current versions of files.

Earlier, we used git add to stage the changes. There’s an easy way to stage all tracked files’ changes and commit them in one command: git commit -a -m "your commit message". The option -a tells git commit to automatically stage all modified tracked files in this commit.

Seeing File Differences and Commit History: git diff and git log

We already saw git diff above (there are obviously, many more options (try git help diff).

We can use git log to visualize the chain of commits. The strange looking mix of numbers and characters after commit is a SHA-1 checksum. SHA-1 hashes act as a unique ID for each commit in your repository. You can always refer to a commit by its SHA-1 hash.

Moving and Removing Files: git mv and git rm

When Git tracks your files, it wants to be in charge. Using the command mv to move a tracked file will confuse Git. The same applies when you remove a file with rm. To move or remove tracked files in Git, we need to use Git’s version of mv and rm: git mv and git rm.

Telling Git What to Ignore: .gitignore

You may have noticed that git status keeps listing which files are not tracked. As the number of files starts to increase this long list will become a burden. To ignore some files (or subdirectories), create and edit the file .gitignore in your repository directory. For example, we can add our empty file there: echo "empty" > .gitignore or a set of fastq file you may have in your data directory: echo "data/seqs/*.fastq" >> .gitignore. Here are some expamples of files you want to ignore:

- large files

- intermediate files

- temporary files

GitHub maintains a useful repository of .gitignore suggestions: https://github.com/github/gitignore/tree/master/Global. You can create a global .gitignore file in ~/.gitignore_global and then configure Git to use this with the following:git config --global core.excludesfile ~/.gitignore_global

Undoing a Stage and Getting Files from the Past: git reset and git checkout

Recall that one nice feature of Git is that you don’t have to include messy changes in a commit—just don’t stage these files. If you accidentally stage a messy file for a commit with git add, you can unstage it with git reset.

Similarly, if you accidentally overwrote your current version of README.md by using > instead of » , you can restore this file by checking out the version in our last commit:

git checkout -- README.md.

But beware: restoring a file this way erases all changes made to that file since the last commit!

Collaborating with Git: Git Remotes, git push, and git pull

The basis of sharing commits in Git is the idea of a remote repository, which is a version of your repository hosted elsewhere. Collaborating with Git first requires we configure our local repository to work with our remote repositories. Then, we can retrieve commits from a remote repository (a pull) and send commits to a remote repository (a push).

Creating a Shared Central Repository with GitHub

The first step of for us is to create a shared central repository, which is what you and your collaborator(s) share commits through. Here we will use GitHub, a web-based Git repository hosting service. Bitbucket and GitLab server hosted by ISU are other Git repository hosting service you and your collaborators could use (both provide free private repositories).

Navigate to http://github.com and sign up for an account (if you don’t have one). After your account is set up, you’ll be brought to the GitHub home page, were you’ll find a link to create a new repository. Follow it and provide a repository name. You’ll have the choice to initialize with a README.md file (GitHub plays well with Markdown), a .gitignore file, and a license (to license your software project). For now, just create a repository named eeob563. After you’ve clicked the “Create repository” button, GitHub will forward you to an empty repository page – the public frontend of your project.

Authenticating with Git Remotes

GitHub uses SSH keys to authenticate you. SSH keys prevent you from having to enter a password each time you push or pull from your remote repository. We create SSH keys on our computer (or any other computer you are using) with the ssh-keygen command. It creates a private key at ~/.ssh/id_rsa and a public key at ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub. You have an option to use a password, but you don’t need to.

However, it’s very important that you note the difference between your public and private keys: you can distribute your public key to other servers, but your private key must be never shared.

Navigate to your account settings on GitHub, and in account settings, find the SSH keys tab. Here, you can enter your public SSH key (remember, don’t share your private key!) by using ``cat ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub` to view it, copy it to your clipboard, and paste it into GitHub’s form.

Connecting with Git Remotes: git remote

Let’s configure our local repository to use the GitHub repository we’ve just created as a remote repository. We can do this with:

git remote add origin git@github.com:your_name/eeob563

In this command, we specify not only the address of our Git repository at github , but also a name for it: origin. By convention, origin is the name of your primary remote repository.

Now if you enter git remote -v (the -v stands for verbose), you see that our local Git repository knows about the remote repository:

git remote -v

origin git@github.com:username/zmays-snps.git (fetch)

origin git@github.com:username/zmays-snps.git (push)

You can have multiple remote repositories. If you ever need to delete an unused remote repository, you can with git remote rm <repository-name>.

Pushing Commits to a Remote Repository with git push

Let’s push our initial commits from zmays-snps into our remote repository on Git‐ Hub. The subcommand we use here is git push

Pulling Commits from a Remote Repository with git pull

To pull the commits from a remote repository, you use the git pull origin master command. Of course pulling them makes sense if somebody else is contributing to the repository. Examples can be your professor updating the course GitHub, you yourself working on two different computers, or several collaborators working on a joint project. In fact, it’s a good practice to always pull before you push!

Merge conflicts

Occasionally, you’ll pull in commits and Git will warn you there’s a merge conflict. Resolving merge conflicts can be a bit tricky, but the strategy to solve them is always the same:

- Use

git statusto find the conflicting file(s). - Open and edit those files manually to a version that fixes the conflict.

- Use

git addto tell Git that you’ve resolved the conflict in a particular file. - Once all conflicts are resolved, use

git statusto check that all changes are staged. Then, commit the resolved versions of the conflicting file(s).

It’s also wise to immediately push this merge commit, so your collaborators see that you’ve resolved a conflict and can continue their work on this new version accordingly.

For complex merge conflicts, you may want to use a merge tool. Merge tools help vis‐ ualize merge conflicts by placing both versions side by side, and pointing out what’s different (rather than using Git’s inline notation that uses inequality and equal signs). Some commonly used merge tools include Meld and Kdiff.